Failures R Us

Seedballs, Willow Wattles, and The Bear Theft Part 3

Tears streamed down all of our faces as Beata prayed in Tewa, the native language of this place.

We were standing in a circle, holding hands and sharing blessings for regeneration and healing for the soil. This was a holy moment. This was a healing moment. Five humans, holding hands, asking for blessings from the ancestors of this land. Asking for guidance from the 400-year old grandmother tree who survived the wildfire. Asking for support from the fungi and invisible mycelial systems to show us how to help heal the land.

We held hands in silence, drinking in this sacred moment. Then we sat down on the earth, and heads close together, gently scooped up dirt and placed it over the quilt.

Each scoopful of dirt was a mixing of prayers and science, hope and study.

What we were burying so reverently was a feast for the invisible. Kaitlin had devised a way to study mycelium, the vast underground fungal networks in the soil. Learning what fungi grew where would help us best tend to the land post-wildfire. (Meet Kaitlin and Beata here: )

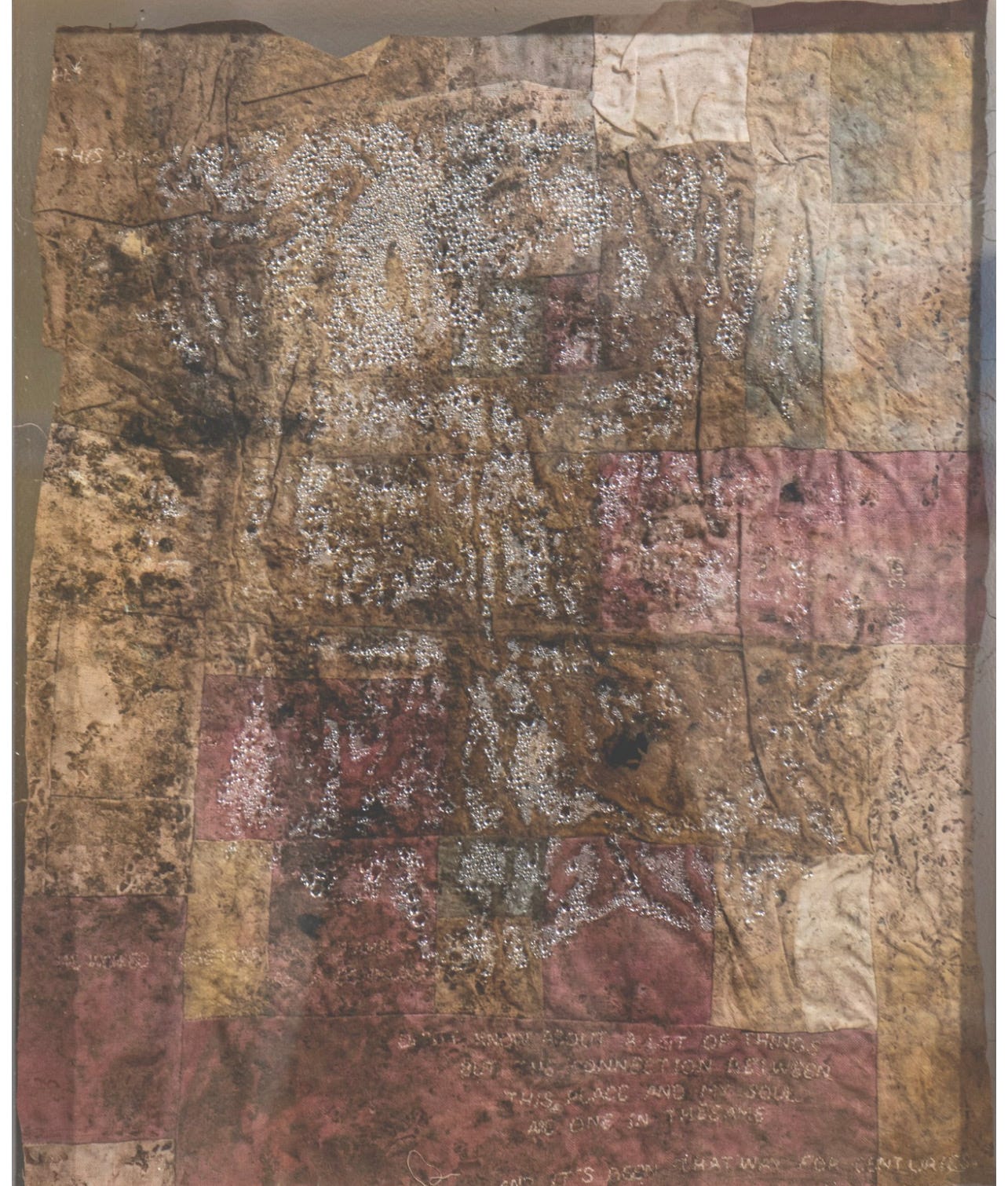

The quilt was a banquet: cloth soaked in honey to entice the fungi, with a tiny pocket packed with cooked rice to give the fungi something substantial to eat. “The honey so they will come, the rice so they will stay,” Kaitlin said.

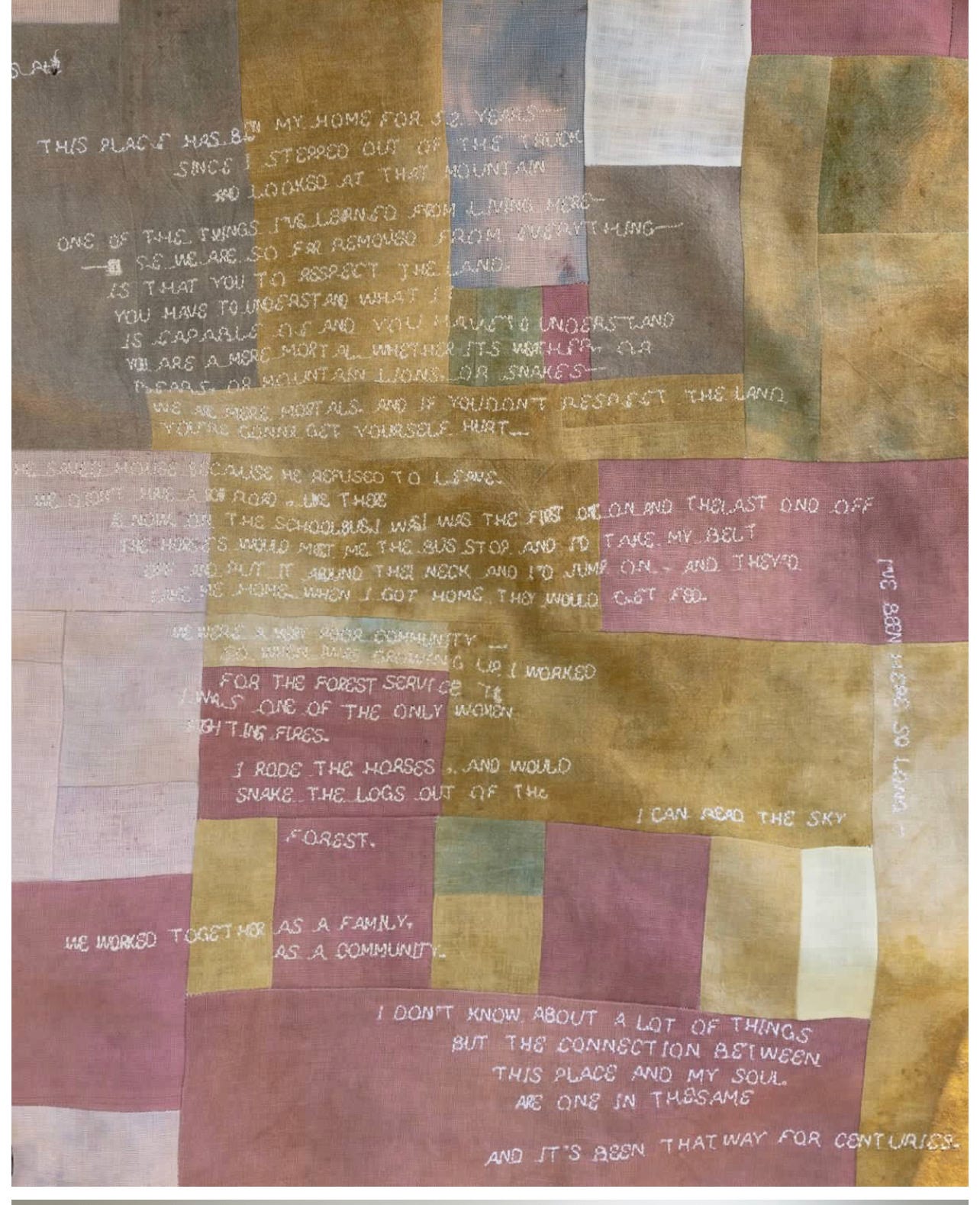

The quilt was also a ceremony: made of hand-dyed linen, stitched with words from those affected by the fire. Hands coming together to place it in the earth, to ask for guidance for next steps.

Kaitlin’s long-term plan was to bury multiple quilts throughout the land, inoculated with fungi from this place. Each mycelial quilt would help restore the fragile soil and forest ecosystem, literally from the ground up.

This was the very first test quilt, buried by the creek near the last standing old-growth tree on the property.

The grandma tree, a 400-plus year old Douglas Fir, is on the northwest corner of the 180-acres of land I steward. Around her is a small group of trees that miraculously survived the wildfire.*

The soil and fungi around the grandma tree’s roots are precious stores of nutrients, ancient wisdom, and medicine for the hundreds of acres blackened and sterilized.

After the burial we leave grandma’s haven and head back through the devastation. It is about a 20 minute walk through Mordor to the next oasis of green forest: a tiny forest remaining of ponderosa pines around our community kitchen, which is at the northeast corner of the land.

For the evening, we are jubilant, grateful to be together, to have taken the next step in healing the soil with prayers and science.

In the morning Kaitlin and a friend hike out to the grandma tree again to check on the buried quilt.

An hour later they are back, bringing news:

“The quilt is missing! Something dug it up!”

The quilt, and all the work that went into our first experiment, was gone 12 hours after we buried it.

I started laughing and shaking my head. “It was the bear!” I said.

I mean: bear, honey. How could the bear resist?

But that was only the first of a series of fabulous failures as we fumble our way to restoration.

The next loss was of the willow wattle.

Okay, let’s first say willow wattle several times quickly. Go! It is such a great combo of words. Willow wattle. Willow wattle. Willow wattle. The words roll around in the mouth like cold marbles on a hot day. Willow wattle.

Willow wattles are weavings of branches anchored on the banks of a creek to help with erosion control. The idea is that the wall o’ willow helps hold soil, and eventually the willows start growing, making a living border.

Two weeks after the bear theft and the willow wattle making came the hail storms.

In June.

During the longest hail storm a small group of us were trapped in the yurt. It was so loud and so unrelenting that we laid down on the floor with our heads towards the center, faces looking up into the center skylight.

The cacophony on the yurt roof was like being inside a drum an enormous being played by drunken maenads.

Through the round skylight, the hail looked like comets streaking towards us, shadows from space moving closer and either zooming past or splatting white on the dome.

Once the storm passed we emerged to a different world. Mud, water, and broken plants and branches everywhere. Our sweet, slow creek rose five feet into an orange-brown churn that gobbled trees and sucked in sand.

It also completely buried the willow wattle. Bye, bye willow wattle! **

And then there were the thousands of seed balls we planted.

Which. Mostly. Failed.

Along with the hail there were several beautiful summer rains to help them sprout, and then two months of scorching summer sun. Instead of our usual monsoon rains in July and August there was only the unrelenting summer sky and wind.

I was in Europe traveling all summer, and I kept checking the weather in New Mexico. Where were the monsoons? Are the new seeds we planted going to survive? Was all that planting just a waste? Should we have waited until fall to plant? What if….

Restoration after damage is almost always slower than we would like. It takes a dedication that goes beyond immediate satisfaction, into pure will and stamina.

Luckily, I have really thorough training from the best.

Funnily enough, my main teacher is fire.

I’ve been leading firewalks since 1991, and I can tell you that there is nothing like wrangling all the components to make a successful firewalk to help you be present and ready for anything.

And yes, I see the incredible irony of being a firewalk instructor devoted to the sharing the immense healing of the fire and losing most of my ranch to a wildfire.

Fire heals. Fire destroys. I still love fire, even while I will spend probably decades tending to its destruction on the land.

Lighting a fire is sometimes effortless, and sometimes nearly impossible.

Fire is alive, its own being, and needs different things to nourish and thrive.

Here is a story of my favorite firewalk near disaster, where we had to seriously woo the fire into being.

The setting: Pacific Northwest. Wet. On a remote island. In a rustic barn. Unseasoned wood. Ferry to catch to get back to the mainland.

Did I mention wet?

I had brought two new fire tenders with me, who were excited to take care of the fire while it burned down to coals. I could see the moment we set flame to wood that we were going to have a struggle getting this wood to light.

I took the group inside, trusting that my fire tenders would get the fire going.

Here was my first of many mistakes: I chose to teach the firewalk workshop in front of a large window that overlooked the fire area. When I picked the spot I thought: Ooooh, this will be beautiful, to have the fire burning behind me, framed by the window.

It was a disaster.

About 30 minutes into the workshop I heard a noise behind me.

Whooooosh!!!!

I closed my eyes momentarily and thought, “Oh, no.”

And then I opened my eyes to watch everyone’s face light up with an orange glow.

I turned around and watched as the gasoline the fire tenders had tossed on the fire whooshed higher and then disappeared.

I turned back to my audience of about 50 people, took a breath, and continued with the teaching.

Whooooosh!!!!

Undeterred by the fact that gasoline is a terrible thing to throw on fire and completely useless beside, the fire tenders continued forward with their ill-fated plan.

I turned back to my audience and start again, knowing I was going to need to find a good place to put them into a partner share so I could go outside and see what was happening.

Again, everyone’s faces momentarily lit up with the glow of gasoline ignited. It was quiet for about five seconds, and then I saw horror on someone’s face as they stared out the window and said, “Her hand is on fire!”

I turned around to see one of the fire tenders running and waving her hand, which is engulfed in flames.

“Everything is okay” a soft knowing fills my body. I don’t know how it is okay that someone’s hand is on fire, but I know instinctually that right now I must trust them to do their job and trust myself to do mine.

I turn back to the audience, knowing if I don’t recapture their attention in the next heartbeat I will completely lose the room and there will be no bringing them back.

I take a deep breath into my feet, and open my mouth. What comes out surprises everyone, including me.

“What is happening out there has nothing to do with you. Bring your attention here. Now.”

50 pairs of eyes turn towards me, and we have a silent moment of acknowledgment. We are here to do the impossible: to walk on fire.

I finish up the next section of teaching and ask them to share with a partner. Then I walk outside to see what is happening with the fire.

My firetenders are ecstatic to see me… “Monica’s glove caught on fire!” They say in unison. “We can’t get the fire going. There is only one coal…”

They point to our pile of wood that should be well into burning towards coals.

Before us is a sad pile of unburnt wood and one, tiny coal glowing in the darkness.

“Okay,” I say. “That is our firewalk. Turn that coal into a fire.”

We again stand in silence, contemplating the task at hand.

They nod at me, and we each go back to our tasks.

An hour later, by a total miracle that to this day I have not idea how they managed, we came out to a bed of perfect coals.

And after a joyous dance across the coals, we all made the ferry to leave the island.

Time and reality bending at its best.

Earlier this week, I had a one coal moment.

Except the coal was one tiny speck of wildflowers from our summer seed ball planting.

The land, as it was last fall, is in places gloriously covered in native flowers and scrub oak. Tall stalks of soft-green mullein, purple daisies, sunflowers, tiny yellow flowers, with sprinklings of red paintbrush here and there.

I mentioned to a friend that it looks like Mordor with flowers.

She said: “Like Mordor and Narnia had a baby?”

Yes, that is it exactly. Imagine Mordor and Narnia have a baby, and you can get a sense of what a forest post-wildfire looks like.

Places along the creek and the island of green around our community kitchen is definitely more Narnia than Mordor. So many flowers it looks like a sea of yellow and purple.

Then there are still acres that are more Mordor than Narnia. Very little is growing back under the black skeletons of trees. The soil is desertfying, the little top soil long ago washed down into the arroyos leaving sand and rocks behind.

Walking through these areas over a year after the fire is still heartbreaking. It feels impossible, that no life can be kindled in this burn scar wasteland.

I didn’t see any evidence of the thousands of seeds we had planted in the spring. Did all of them die? Is the soil so destroyed it will not sustain new life, and will just be a barren landscape?

And then, I saw hope glinting in the distance.

In a small dip in the sand and rock a tiny patch of wildflowers sprouted from the seedballs we planted in the spring.

Dark purple bachelor buttons. California poppy. Red poppy. Cosmos. Orange daisies. A grass heavy with seed pods.

Leaning down low, tears in my eyes I said “Hello, friends.”

Despite all the failures: We have our coals.

* The Calf Canyon / Hermit’s Peak fire, which started 30 miles away in April 2022, devoured half a million acres and burned over three months. It was the largest wildfire in New Mexico history.

** This weekend I noticed two tiny willows growing from the either side of 1/2 inch of willow wattle poking up from the sand. YAY! It worked!

GRATITUDE to those of you who have donated, prayed, loved, and supported the slow restoration process. Out of the approximately 3,000 seedballs we made and 15 pounds of grasses and wildflowers we planted, I guesstimate that 50 flowers and grasses survived the summer. WE HAVE WILDFLOWER AND GRASS COALS, friends! And while the land and the winds are doing their job spreading native seeds, I’m dedicated to gently and steadily blowing on the seeds and fungi and trees we plant to bring the fire of healing to the burn scar.

Over the next month I’ll be expanding my writing in Out of the Fire to other contradictions and explorations. I’ll also continue sharing regular updates on Warrior Heart Ranch, our wildfire restoration project, and our continued slow and steady building projects.

Current projects for the land: Planting more aspens along the creek. Erosion control on hills, arroyos, and the creek. More fungi testing and cultivating. Fall seedball and seed plantings. Tree planting and figuring out how to get them water in remote areas. Making swales and digging out shallow areas to slow down and retain rainwater and give seeds a better chance of survival.

Current projects for the humans: The new bathhouse which we started building in June now has the first coat of stucco and the bathrooms and showers rooms are ready to be tiled / painted. The vertical supports are burnt trees from the land.

And our new mill is now set up and we are starting to harvest the burnt trees and transform them into milled lumber for cabins.

SPECIAL THANKS to those of you who are paid subscribers to Out of the Fire. Your belief in me and monthly or yearly contribution truly helps keep me going.

A LIBRA BIRTHDAY REQUEST: please consider becoming a paid subscriber, or unleveling to becoming a founding subscriber of Out of the Fire.

You can also donate directly to the restoration fund for buying Fall seeds via Venmo @creativeintent or PayPal. Any amount helps. All donations are tax-deductible through our 501 (c) 3, the Center for Creative Intent.

And keep blowing on the coals in your life and kindling the fires of your creativity, healing, and love.

Slow and steady, beloveds. Let’s do the impossible.

Seedballs, Willow Wattles*, and The Bear Theft Part 2

March 1, 2023 “What I do is a little bit weird,” she told me. “Try me. I’m guessing anything you share will not be weird to me,” I responded. Wonderful, wild, visionary, amazing, creative genius… those are the words I would use to describe Kaitlin and her work. Definitely not weird.

Seedballs, Willow Wattles, and The Bear Theft Part 1

A seedball is a little universe in a marble-sized package. As I held it in my hand, feeling the clay smooth against my palm and the seeds held within, I felt a sense of peace click back into place that I hadn’t felt since the previous April. I’d found what I had been seeking.

A wonderful story of beauty, resilience, and perseverance. Rock on Sister.