Seedballs, Willow Wattles*, and The Bear Theft Part 2

The remediation, the roots, and the relief

March 1, 2023

“What I do is a little bit weird,” she told me.

“Try me. I’m guessing anything you share will not be weird to me,” I responded.

Wonderful, wild, visionary, amazing, creative genius… those are the words I would use to describe Kaitlin and her work. Definitely not weird.

But I could see why she gave her “weirdness ahead” disclaimer before she shared about her project, Bellow Forth.

Here we enter a world that I didn’t even know existed — a world that seamlessly blends soil restoration, mycelium, fungi, science, and art.

My prayer for the land was huge and beyond the scope even of my imagination: that while we healed the land we helped heal the world.

As I sat with Beata and Kaitlin that first meeting surrounded by seeds and plants specifically for the southwest, I realized I was being connected to a sacred gathering of cutting edge science, indigenous wisdom, and wild creativity.

… Read Seedballs, Willow Wattles, and the Bear Theft Part 1 here ….

In Braiding Sweetgrass author Robin Wall Kimmerer — mother, scientist, decorated professor, and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation — speaks to this importance of shifting our perspective completely:

In the Western tradition there is a recognized hierarchy of beings, with, of course, the human being on top—the pinnacle of evolution, the darling of Creation—and the plants at the bottom. But in Native ways of knowing, human people are often referred to as “the younger brothers of Creation.” We say that humans have the least experience with how to live and thus the most to learn—we must look to our teachers among the other species for guidance. Their wisdom is apparent in the way that they live. They teach us by example. They’ve been on the earth far longer than we have been, and have had time to figure things out.

~ Robin Wall Kimmerer

Drawing on her life as an indigenous scientist, and as a woman, Kimmerer shows how other living beings--asters and goldenrod, strawberries and squash, salamanders, algae, and sweetgrass--offer us gifts and lessons, even if we've forgotten how to hear their voices. In reflections that range from the creation of Turtle Island to the forces that threaten its flourishing today, she circles toward a central argument: that the awakening of ecological consciousness requires the acknowledgment and celebration of our reciprocal relationship with the rest of the living world. For only when we can hear the languages of other beings will we be capable of understanding the generosity of the earth, and learn to give our own gifts in return.

~ from Braiding Sweetgrass.

I had been gifted with meeting two women who were exploring and creating healing not from a disconnected scientific analysis but from deep respect and connection to the land and thousands of years of indigenous wisdom.

Their friendship deepened through numerous projects over the years, including the founding of the Española Healing Foods Oasis through Tewa Women United and compiling Mycology and Mycoremediation: Information and Guide for At-Home Mushroom Cultivation for Remediation.

Here is a simplified overview of Kaitlin’s project Bellow Forth, which was being funded by Anonymous Was a Woman Environmental Art Grants in conjunction with the New York Foundation for the Arts and was in collaboration with Beata:

- Gather stories from people and communities who had been affected by the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon fires

- Stitch these stories into a quilt made of cloth hand-dyed with local herbs and plants

- Stuff the quilt with cotton batting seeded with local fungi

- “Plant” the quilt with prayers and intent in an area affected by the wildfire

- Test the soil before and afterwards to see if prayer and focus enhances the soil restoration process.

Kaitlin had already done several story circles in San Miguel county. Now she was looking for places to test soil and bury the quilt.

I took Kaitlin’s hands, squeezed them, and said to her and Beata:

“My land is your land. Truly.”

Please use it in anyway that would be helpful, I said to them. It is such sacred land and I want it to be restored in a sacred way.

“I’ve seriously been waiting for you both. Thank you for what you are doing, it is so needed. I feel so honored to meet you both.”

We parted with hugs and an agreement to meet up on the land within the next month.

When I got back in my car I cried tears of relief. And when I got home I looked up Kaitlin’s website and cried some more.

Kaitlin Bryson is a queer, ecological/bio artist concerned with environmental and social justice. She primarily works with fungi, plants, microbes, and biodegradable materials to engage more-than-human audiences, while also facilitating human communities through social practice and environmental stewardship. Her practice is research-based and most often collaborative, highlighting the potency of working like lichens to realize radical change and justice. In 2019, Bryson co-founded The Submergence Collective, an environmental arts collective focused on multidisciplinary projects that imagine more collaborative, creative, hopeful, and ecologically connected futures for our human species and the rest of the living world.

Bryson received an MFA in Art & Ecology from the University of New Mexico in 2018, where she concurrently studied art and mycology with research in ecotoxicology. Currently she works as a practicing artist, land-steward, and radical educator.

The land had called in the needed healers.

March 24, 2023

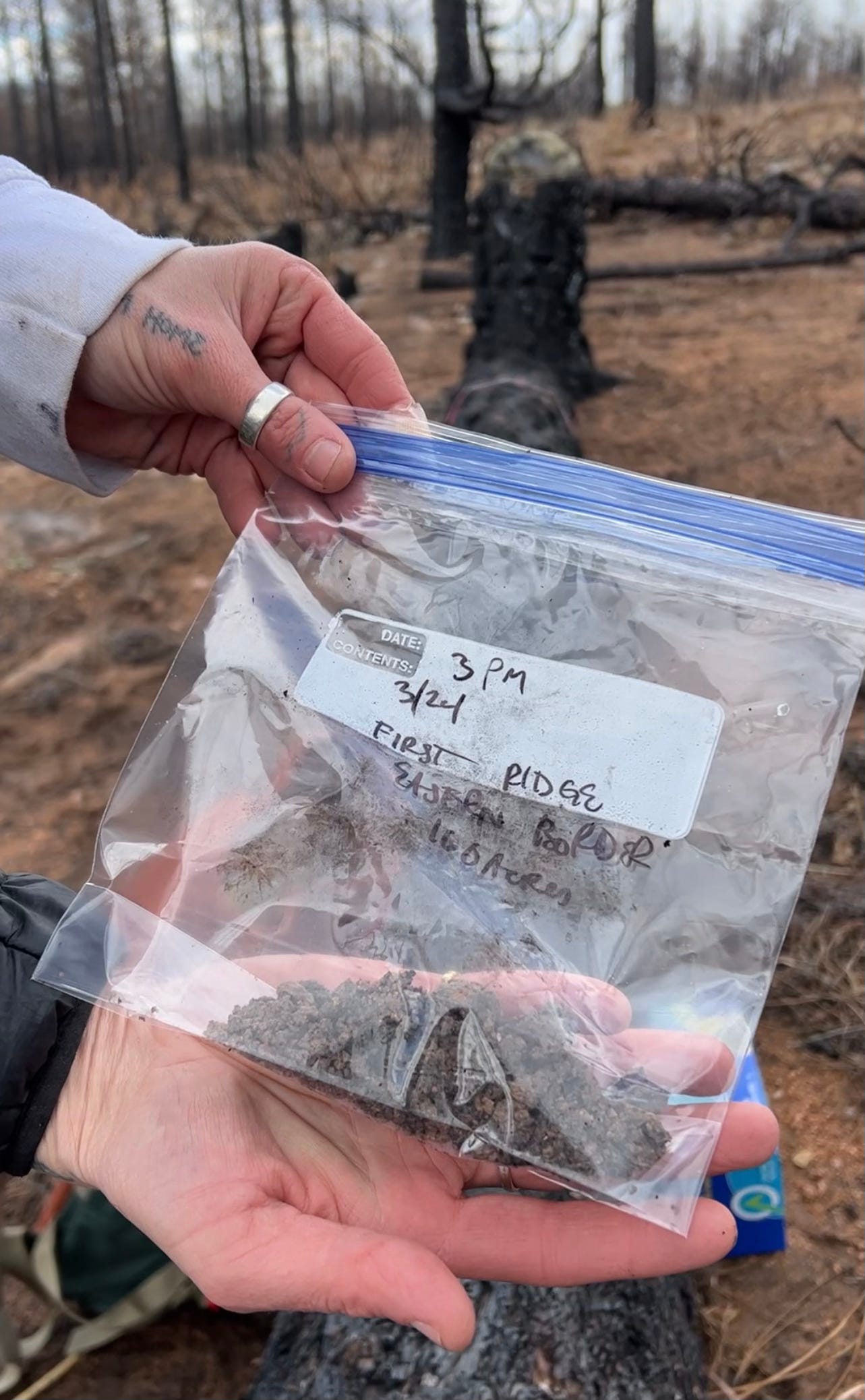

Kaitlin and I met up on the land a few weeks later. She brought her soil sampler with the intent of testing soil from different places on the land. The samples would then be sent to the lab to test for concentrations and types of fungi in the soil.

We were making coffee in the kitchen and talking about her project when it started snowing.

We looked at each other and started laughing. Of course it would snow on what started as a clear, sunny day.

“Are you still up for a walk?” I asked. “Of course!” She responded. We were both wilderness women, not afraid of a little snow.

But damn, was it cold!

We traveled through sometimes white-out conditions, stopping every once in a while to take soil sample. Soil samples from the edge of the burn area. Soil samples in the worst areas of the burn. Each sample was placed in a baggie and marked with location, date, and time. We took videos and pictures and laughed about the windy, cold, snowy conditions as we trekked.

Here is a video of our first soil sample, which ended with a very dramatic dog fight between our two dogs. I edited that part out : ) After that fight our doggies were best friends.

After the first two samples the snow picked up considerably, and we kept our heads down until we got to the grandmother tree.

At the grandmother tree we took off our packs and sat, and I shared my story of coming to the land for the first time post-wildfire.

“I had one destination,” I said, “Which was to see if the grandmother tree had survived.”

May 20, 2022

We had sent scouts out to ascertain how bad the burn was: My partner Franklin, my friend Mark, and Ernesto, who had spent the last year thinning the pine trees up on the land before the fire went through.

I was sitting on the porch when they returned, and knew it must be really bad when Franklin didn’t come up to talk to me, but Mark did.

Mark sat next to me, took a deep breath, and said:

“There is no easy way to say this. My guess is that 1 percent of the trees survived.”

Franklin told me later that the devastation was so profound that he felt completely shaken for days afterwards.

Early the next morning I left before sunrise and drove by myself up to the land. I needed to see it for myself, without anyone else around.

As I hiked I had one prayer: “Please let the grandmother tree be alive. Please let the grandmother tree be alive. Please let the grandmother tree be alive.”

After acres of black I saw one small ponderosa pine in a sheltered area that had survived, and then acres more of black. I came to the arroyo where the grandmother tree grew, took a breath to steady myself, and headed north.

Along the way I passed smoking holes where roots were still burning. I clambered over blackened rocks and soil. I cringed at the amount of blackened, dead trees all around.

“Please let the grandmother tree be alive. Please let the grandmother tree be alive. Please let the grandmother tree be alive.”

The tree I call the grandmother was an enormous Douglass Fir, somewhere between 400 to 500 years old, who lived on the southwest corner of the property. Nearby her was another large Douglass Fir I called the grandfather tree.

Up ahead I could see that the grandfather three had been severely burned on one side; half of its needles were brown from heat, and half were still green. I hugged its massive trunk and whispered to it, “I am so sorry. Please live.”

Then I continued to walk, slowing down in fear of what I would find.

“Please let the grandmother tree be alive. Please let the grandmother tree be alive. Please let the grandmother tree be alive.”

And she was. The soil around her was black and many of the trees nearby were dead, but somehow she was completely untouched by the fire.

When I saw her I knew it was going to be okay, that there some grace in this horror of destruction.

Here is the video I took that day at the grandmother tree:

Kaitlin and I looked at each other, tears in our eyes after I shared my story.

“It is amazing she survived. We’ll sample soil right here, and then we can use the soil around the grandmother tree to help restore the land.”

And so the grandma tree, who has seen many fires in her time and who has the strongest mycelial network, will be the center of healing the land.

Later we would return to the grandmother tree with Beata, Franklin, and my friend Marilyn to say prayers and bury one of the quilts Kaitlin had made in the rich soil by the creek.

It was a ceremony I’ll never forget.

The bear loved it, too.

Meet Baxter the Bear below and read Part 3 of Seedballs, Willow Wattles, and the Bear Theft: Failures R Us.

RESOURCES

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants

Bellow Forth is a community project focused on restoring soil health and environmental resiliency through storytelling and collaboration, community and ecosystem science, and social art practice in wildfire-impacted lands and communities in northern New Mexico. In 2022, nearly 350,000 acres were burned in the Calf Canyon and Hermit’s Peak wildfires, the largest wildfire in New Mexico’s state history.

This project is multi-specied and multidisciplinary, imbricating biodiverse soil systems with human stories to foster relationships, facilitate succession in post wildfire landscapes, and embed a deeper appreciation for and accountability to the diminishing, living world.

The project is largely inspired by the poem, “Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude” by Ross Gay, which catalogs Gay’s experiences of place, life, family, and love that he wants to thank, acknowledge, and praise. The poem begins with a recounting of a dream where he is called by a robin to “bellow forth” a long list of gratitude that is an authentic gesture for loving and singing for, “what every second goes away.” To honor and catalog what was lost during the Calf Canyon and Hermit’s Peak wildfires last year (and what is continuing to disappear due to the climate crisis) the project aims at creating a similar catalog of gratitude through community stories. However, these stories are embroidered into a large story quilt and will be offered to the ground to restory* the soil.

*We are grateful to the author/legend, Sophie Strand who led us to this term and magic ;)

The story quilt will be inoculated with nutrients to attract native fungi and microbes who are essential for soil and land regeneration. Healthy ecosystems and communities begin in the soil; if there is a thriving population of fungi and microbes, there is a better chance at future successive processes, water retention, and native plant establishment.

Part 2 1/2 of Seedballs, Willow Wattles, and the Bear Theft

Let Me First Introduce Baxter the Bear

Let me introduce the bear. But first, some context. The 180-acres of land I steward is miles down a side road off I-25, about 75 minutes from Santa Fe heading towards Colorado. Turn left over the freeway through two rock ridges and a windy road that gains in altitude.

Oh my goodness!!! I FREAKING LLLLOOOOVVVVEEEEEEEEE that the Grandmother tree is used as "ground zero," the way forward, to repopulate. That brings tears to my eyes and makes my Soul sing. Thank you for sharing!!! XO

It's Stephanie Sullivan HeatherAsh, and I am also heartbroken for the tragedy of the fire.

I an writing to say that someday I would love to co.e visit, even help, as I have many skill.

Love & Light,,